The Integration of Sarasota Beaches

Overtown and Newtown residents faced the harsh challenges of Jim Crow policies upon arrival in Sarasota, where, until the 1960s, segregation prohibited black residents’ access to public accommodations. An indomitable spirit led them to resist this discrimination.

Newtown is a special African American community that grew out of another community. Overtown was the first enclave or neighborhood established by African American residents in Sarasota, Florida. Three institutions were most important: school, church and home.

Most of the new arrivals in Sarasota came looking for a way to better their lives. From the onset, they faced the stiff challenges of racism and segregation. They had to work menial jobs, even with an education.

Clearly, an indomitable spirit emerged out of their struggle. They had a strong faith that brought them through many challenges. Church services were held in homes initially, until sanctuaries were constructed that served as the community’s foundation. Children were educated there and churches were places where residents could exercise control over their own destiny and build self-esteem. The segregated south did not provide such amenities.

(above) Residents with cars traveled to Caspersen Beach in Venice many miles away from home. Suzie Johnson is pictured. Quessie Hall and Ruby Sims Collection.

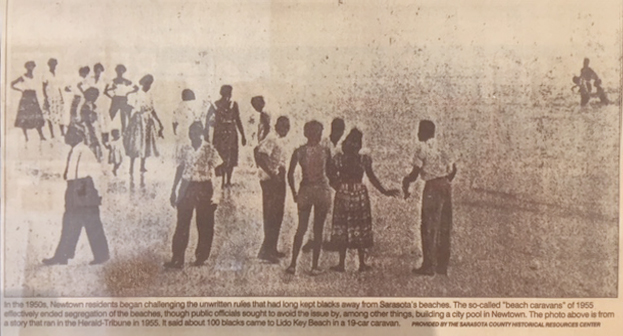

(above) An iconic 1955 photo of Newtown residents who began showing up in car caravans to Lido Beach for “wade-ins.” There were unwritten rules that closed beach access to African Americans. Courtesy: Sarasota Herald Tribune.

(above) Newtown children swam in neighborhood swimming holes after rainstorms. Nearby beaches were off limits. Jetson Grimes Collection.

(above) From left is James Sims and Bert Irons at Caspersen Beach, 1956. Jetson Grimes Collection.

Before the rise of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as the leader of the Civil Rights Movement, Sarasota’s African American leaders voiced their demand for equal access to county beaches.

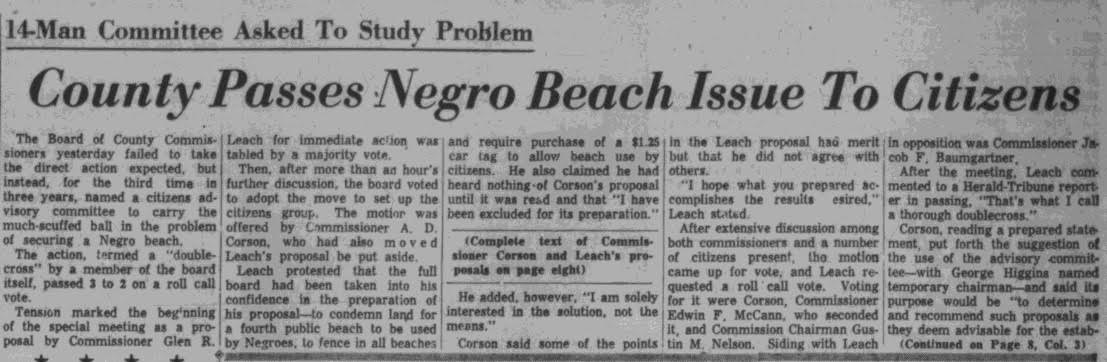

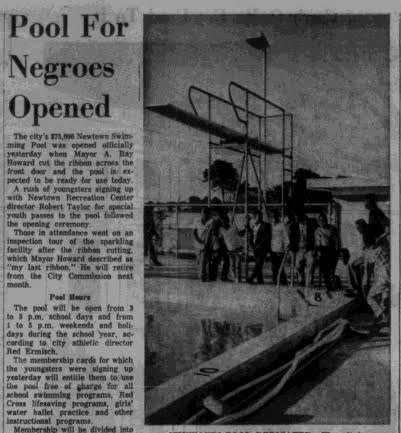

In 1951, Newtown business owner Mrs. Mary Emma Jones requested a beach for “colored residents” at a Board of County Commissions’ meeting. Facing opposition from white residents, local lawmakers proposed instead to construct a swimming pool in the African American community.

After no action on beach access was taken in September 1955, Sarasota NAACP President Neil Humphrey Sr. led a “wade-in.” Newtown residents piled into cars, drove to Lido Beach, swam and walked its shores. About 100 residents repeated the protest in October.

Mr. Humphrey, his NAACP successor Mr. John Rivers, activists and residents continued publicly asserting their rights to access beaches.

Although the Civil Rights Act banned discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin in 1964, it took several more years before the beaches were integrated.